December 21, 2022, Jim Phelps went to work just like anyone else would have — fully prepared for the major winter weather event on the way.

At least he, and so many others, believed.

Plant manager for the Tennessee Valley Authority’s massive Paradise Combined Cycle facility in Muhlenberg County’s Drakesboro region, just outside of Central City, Phelps had seen the forecast: lovely, unseasonably warm mid-week temperatures, followed by a cold arctic blast accompanied by crippling precipitation.

Denoted by some as “Winter Storm Elliott,” TVA’s power grid — covering seven southeastern U.S. states — seemed impervious, never before stressed beyond its limits.

However, over the next 36-to-48 hours, thermometers plummeted to sub-zero evenings and single-digit days.

Phelps remembers it reaching minus-6 a handful of times deep inside the facility’s campus — many of its external implements exposed to things they couldn’t handle.

As such, peak production fell from 1,100 megawatts an hour to around 800 megawatts an hour, a decline of more than 25%. Though the plant never faced shutdown, the entirety of TVA experienced similar issues at multiple locations — as the blizzard buffeted everything from the Mississippi River to the eastern seaboard.

For the first time in its 90-year history, TVA officials had to ask their local agencies to sincerely throttle usage — leading to rolling restarts, brownouts and a handful of blackouts in the News Edge listening area.

What’s more, noted Phelps and Pennyrile Electric’s Michael Oglesby, is that things were very nearly worse.

A manager of key accounts for Pennyrile Electric, Oglesby said that once he got the phone call, he knew TVA leadership was deep inside its multi-tiered “load curtailment plan.”

Looking to avoid such asks in the future, the electric giant has invested more than $120 million this winter to address winter reliability issues across its coal, gas and hydroelectric fleets. Another $120 million is earmarked for fiscal year 2024.

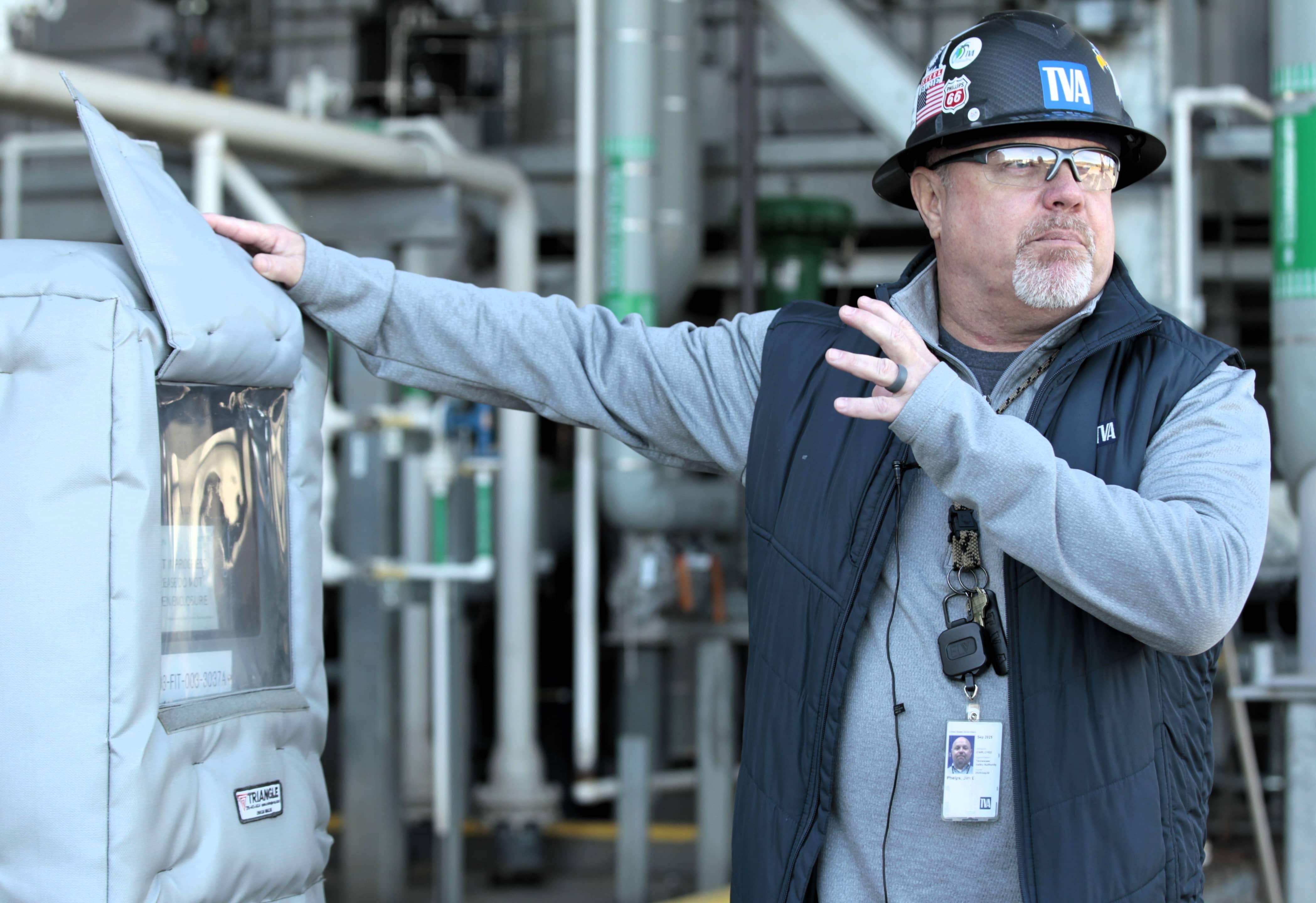

Of that budget line item, Phelps said more than $1 million alone has been spent and implemented in Drakesboro for heat tracing measures, with many other efforts coming in the wake.

In order to fathom the amount of instrumentation, piping and infrastructure open to the natural elements, one must first understand the plant’s size and capability.

Three combustion turbines, powered by natural gas, are attached to a generator, and simulate what Phelps called a “really large jet engine.” Each turbine is capable of creating 240 megawatts.

From there, exhaust measured north of 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit is captured in three different waste heat recovery steam generators and then funneled to make a new steam which boils water.

That steam, generated at no extra cost or power from the plant, turns a dry-housed turbine capable of discharging 450 megawatts.

Unlike coal-fired boilers, the system is ideal for quickly throttling power for low- and high-usage valleys and peaks, uses fewer fossil fuels and comes with few demerits.

However, this facility opened in 2017, and like most of the country, had never been pressure-tested for extreme weather — something Phelps noted is becoming far more common in west Kentucky.

Pennyrile Electric, and west Kentucky in general, has been waylaid over the last 48 months — including a pandemic, three serious tornado outbreaks, a winter storm and wind storm that did more damage than the 2009 ice-pocalypse.

Oglesby noted the efforts needed to surmount these challenges included many from across the country.

At the height of “Winter Storm Elliott,” Phelps noted that megawatt units were being sold back to TVA for “thousands of dollars,” as the need to purchase power became more than urgent.

FULL PHELPS AUDIO:

FULL OGLESBY AUDIO:

STEAM:

STEAM TURBINE

DRAKESBORO

No data found.